Unfortunately, I have never won a prize for running and I probably never will. But that doesn't mean you can't put your own achievements in the spotlight every once in a while. An adventure in bronze casting.

Without our excellent gluteus maximusman would probably never have been able to run so fast. The gluteus maximus, also known as the butt muscle, is necessary to keep our upper body stable when the knees are raised. This muscle is also very different and much bigger in humans than in monkeys, which gives more possibilities for hip and torso flexion. During walking, the gluteus maximus is used relatively little on straight stretches, but during climbing and running it is used extensively. The evolution of our buttocks is probably what made the ape an endurance runner according to Daniel Lieberman.

A fascinating fact, I think. When Bart Stok offered to make a plaster cast of a body part during the auction for course center Kasteel De Schans (see also my earlier article), I was intrigued. But I feared a bidding war and also wanted the photo shoot. In the end I was able to make a deal and a little later Bart even managed to convince me that it was a much better idea to make bronze instead of plaster. I'm glad he did. Not only because of the end result, but it was also a fascinating process.

The imprint

It was a nervewrecking day. Not so much because a plaster cast of my buttocks had to be made as a mould, but because I made an absolute rookie mistake when it came to diabetes. I had prepared my whole bag and then somehow forgot to bring the insulin pen. Very inconvenient when you arrive at lunchtime after a few hours on the train. I was considering to go back, or see how things went without eating, but fortunately Bart turned out to live at a terrain with a workshop and houses for artists in residence, and it turned out that bronze caster Loek Hambeukers could lend me a pen with insulin (no Fiasp, but other short acting will do the trick as well).

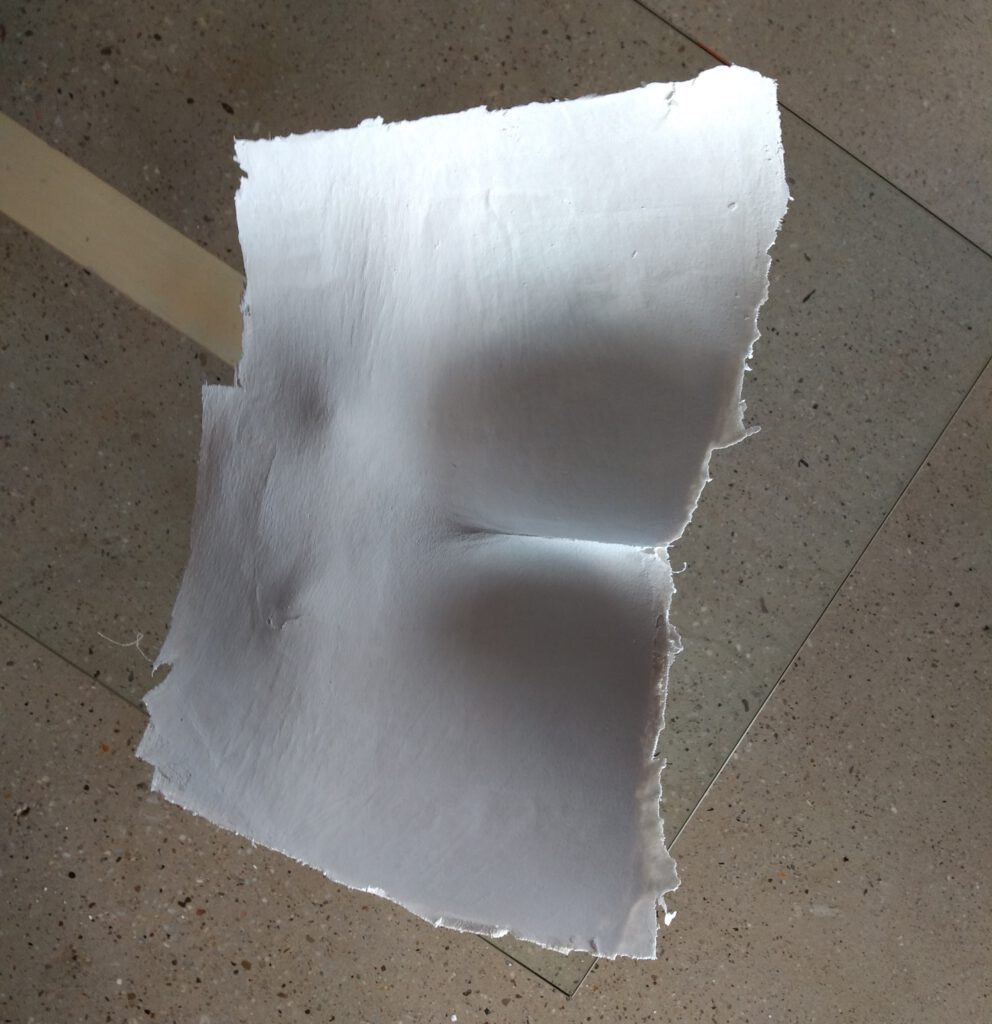

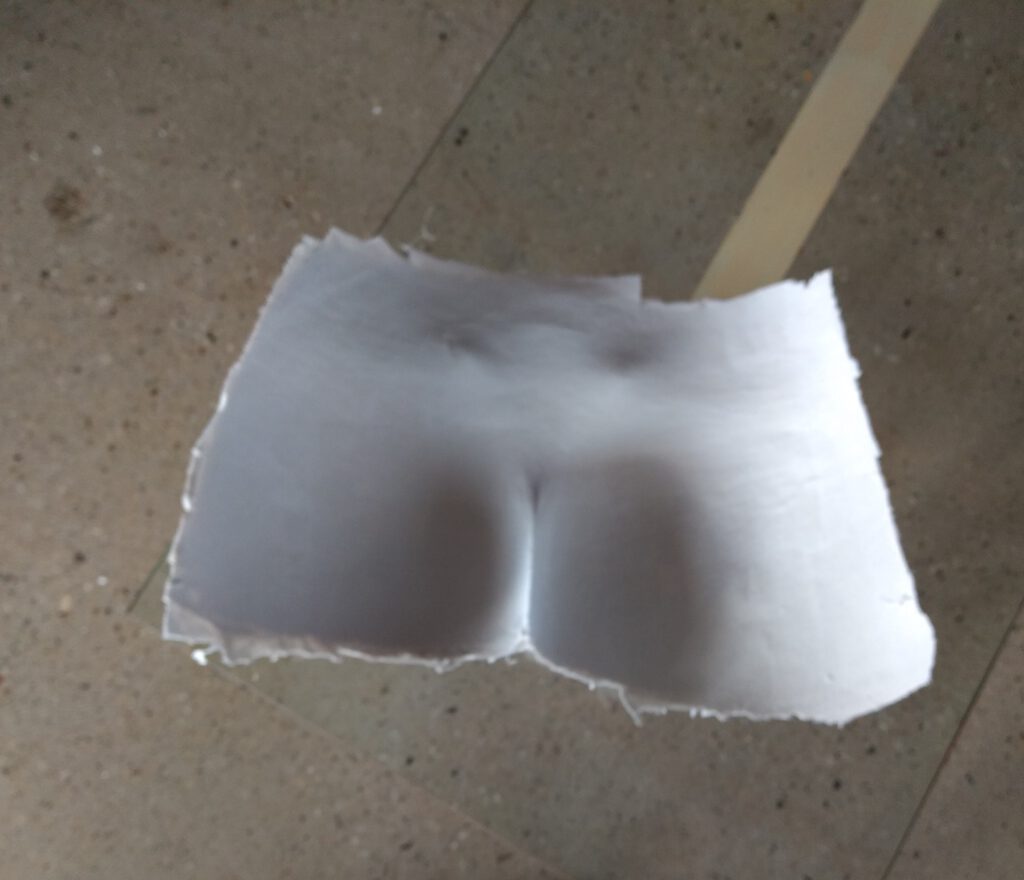

Once I had recovered from the stress, it was a simple matter of lying still for 20 minutes until the plaster hardened. Bart applied the plaster with plaster wraps that he cut into pieces. You make these wet and then stick them to the skin. Because of the weight and the drying time, it was better to do that lying down. Unfortunately, this does mean the buttocks look a bit flatter because there is no tension on the muscle. But my butt is big enough for the random viewer not to notice.

It is also a very strange sight to see a negative of your own buttocks lying on the table. Because of the shadows in the white plaster, it almost looked like they were really there: negative almost became positive. And the nice thing is, you can still see all the pores and irregularities of the skin in the plaster, which makes them really come alive.

On the way to bronze

That first plaster mold is only a very small step in the process. To make a bronze sculpture you need a lot of time, patience and skill. The nice thing is that Bart kept me informed about the steps the sculpture underwent.

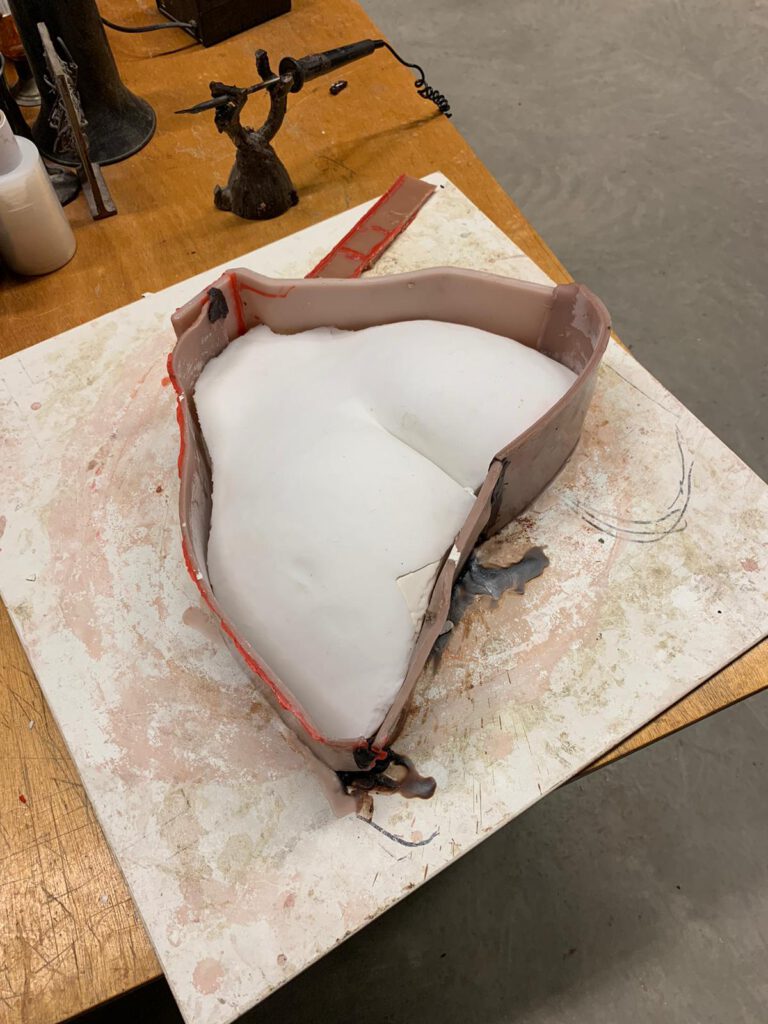

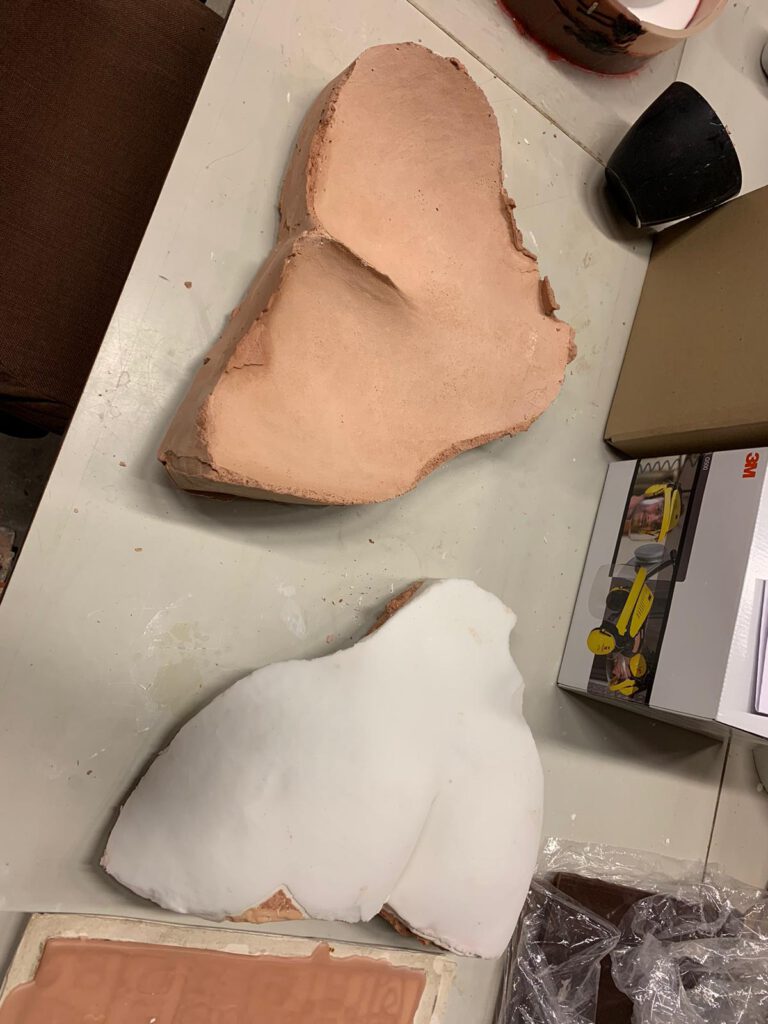

After the mould has dried, the ‘backside is thickened’ (and thanks Bart) with plaster, so it's a bit firmer and a mould can be made. To do this, first put a layer of wax on the plaster to delineate a nice shape, and then spread three layers of silicone on it and put a support cap of plaster over the back of the silicone. The final result is a positive silicone butt which can be used as a reusable mould.

In the next step another border of wax goes around the silicone and you put a mixture of plaster and gravel over it. When this layer of plaster has dried, the negative mould is finished. You then apply wax again, add the casting channels and air vents and put the whole thing in a container with plaster gravel. This all needs to go into the oven for over a week, so that the mould hardens and the wax slowly melts away, leaving a cavity for the bronze.

Red-hot bronze

Unfortunately, all the intermediate steps were done remotely, but I was looking forward to the day that the bronze would actually be cast. How often do you get that chance?

It was a good thing the train was not delayed that day. The melting of the bronze – hours in a melting furnace – apparently went very well and almost simultaneously with my arrival everyone was ready for the first casting. Both castings would contain a version of my buttocks; the silicone mould in the workshop had in the meantime already caused the necessary hilarity among the ladies present. In other words, everyone was curious how those would come out of the mould.

Those moulds of plaster and gravel are very vulnerable when they come out of the oven. That's why they were all placed in a large container with compacted sand (Brussels earth), so that they don't fall apart when the bronze is poured into them. At the top, the moulds all had a hole with a thin piece of shrink foil over it to prevent contamination where the bronze would be cast. To this end, three men in fireproof suits with large sticks – 1.5m is automatically assumed here – carried a heavy crucible with bronze. A single statue easily takes up a few kilos.

It's amazing how fast the pouring goes. A red-hot mass pours out of the crucible, a few flames rise to the surface (the plastic?) and in no time the mould is full. The cooling bronze is very nice by the way: it has a very special glow.

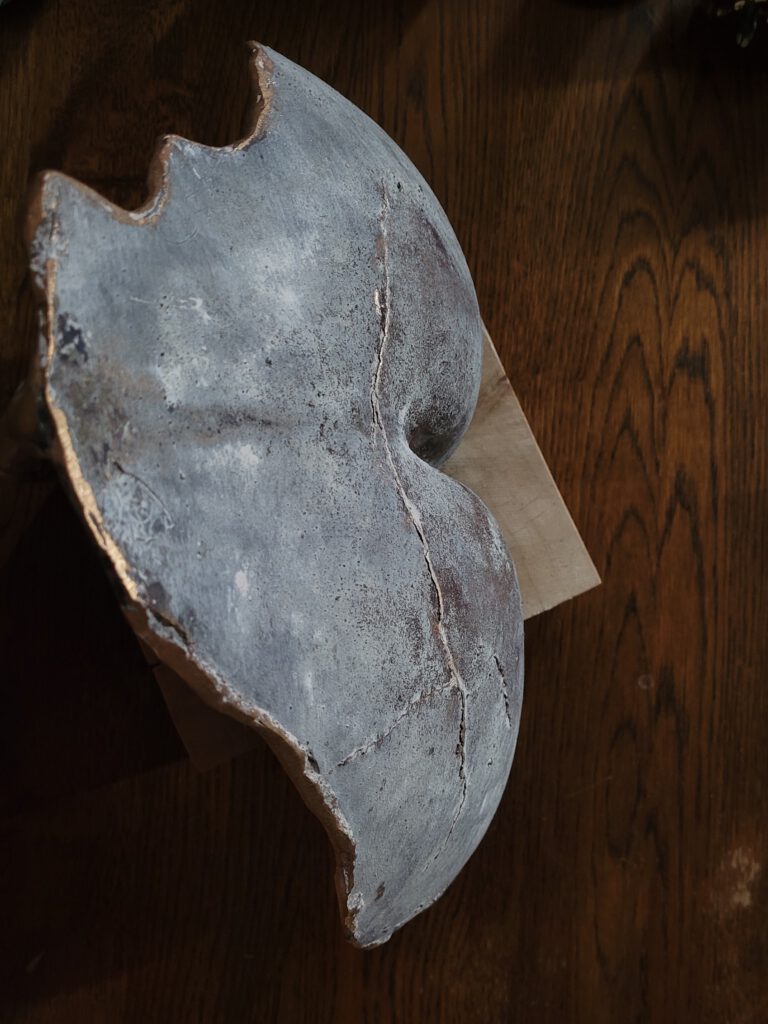

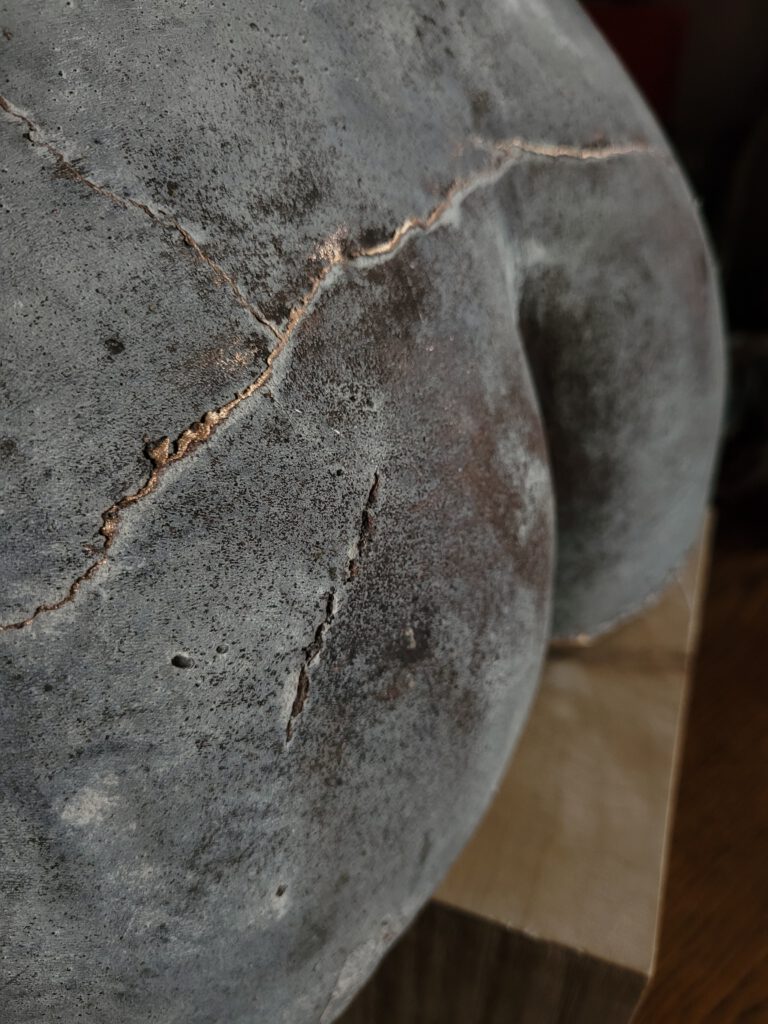

After an hour of cooling down and a lunch, we took the mould out of the bucket and the chiselling could begin. Going at your own bum with a hammer, who would have ever thought that... Slowly the shape appeared, but it was hard work. A few taps against the casting rods also helped to loosen the plaster from the bronze. Finally it was a matter of cleaning the statue with a high pressure jet. That resulted in a very nice bronze: because of the plaster in the mould, the bronze itself is a bit blue-grey in colour, and under the water that gave a deep blue colour.

Finishing

Who now thinks that the sculpture is already finished, is unfortunately wrong. In the last steps, again only done by Bart who I think put a tremendous amount of work into it, the sharp edges have to be removed, the sculpture has to be touched up and made ready for its final destination: a base, a suspension system, or flat on the table with all casting channels completely removed. The sculpture can also be patinated.

In my case, two sculptures were cast. One slightly thinner than the other, as the thickness can have a special effect in terms of edges, but also can lead to holes in the bronze. I myself had chopped the thicker version free from its mould. That was the deciding factor for me to finally choose that variant, as it was quite difficult to decide between the two.

After that choice came the last step: patination. By patination (actually heating) you can change the colour of the work slightly: the bronze gets a green layer. I myself found the blue-grey colour very special. The sister, which stayed behind in the studio, is patinated. Unlike mine, which has a wooden base, it was made to hang on the wall.

Meanwhile the statue has been brought home and is on the table. I'll have to take another good look to find the best spot for it. But I'm quite proud of the end result. And I'm already thinking about modelling a sculpture myself. It seems nice to be able to cast my own work, now that I've seen the whole process.